In the bustling heart of Rawalpindi lies Gawalmandi, a neighborhood that carries two centuries of Pakistan's rich, multicultural history within its narrow streets and aging structures. This unique area stands as a living testament to a time when diverse communities built their lives together, creating a tapestry of interfaith harmony that remains relevant today.

A Legacy of Coexistence and Shared Spaces

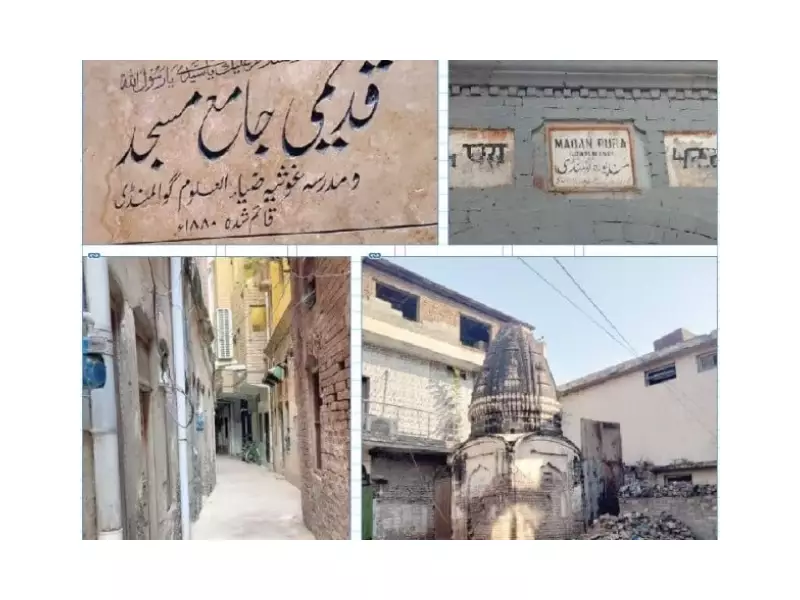

Gawalmandi represents an extraordinary chapter in Pakistan's urban history as the only residential and commercial locality where Hindus, Sikhs, Muslims, and Christians have lived together since its establishment 200 years ago. The area still contains physical evidence of this shared heritage through century-old temples, churches, gurdwaras, and the historic Jamia Mosque constructed in 1880.

The neighborhood's very name originated from its two major milkmen who maintained large herds of buffaloes and sold pure milk, earning the area its identity as "the milkmen's market." Throughout its history, wealthy families and traders preferred Gawalmandi due to its strategic location near wholesale markets, Raja Bazaar, Liaquat Bagh, the railway station, and major business centers.

Architectural Heritage in Peril

Walking through Gawalmandi today reveals narrow three-foot-wide streets lined with two- and three-story houses constructed from wood, clay, and brick. These structures represent exquisite examples of 150- to 200-year-old architecture that blend European and Mughal design elements in their windows and doors, though many now stand in crumbling condition.

Among the most prominent heritage buildings is the Sehgal Haveli, built by Dhan Raj Sehgal in 1910 across four kanals of land. Today, this architectural gem suffers from severe disrepair, having been illegally occupied by impoverished families. The once-magnificent structure now hosts bats, rats, and accumulated garbage after years of neglect, with scavengers having removed much of its bricks, wood, and iron.

The religious landscape of Gawalmandi has also transformed significantly over time. While the area once housed five Hindu temples, only two remain following the Babri Mosque incident—one in ruins and two converted into residences. Four mosques continue to function, including the Jamia Mosque from 1880, while the 130-year-old Sikh gurdwara has been repurposed as a school.

Vanished Landmarks and Cultural Shifts

Many of Gawalmandi's historic landmarks have disappeared or transformed beyond recognition. The site of today's Akbar Market was originally a Hindu cremation ground where bodies were burned and ashes scattered in what was then a clear stream—the present-day Nullah Leh. Adjacent to this stood a large dhobi ghat where freshly washed colorful clothes once decorated open spaces.

The area also hosted a children's park that remains functional today, though it once stood beside a "Parda Bagh" or women's garden jointly maintained by Muslim, Sikh, Hindu, and Christian communities. This unique shared space has since been replaced by a girls' college.

From the 1970s to the 1990s, Gawalmandi gained fame for its vibrant food culture, with tea stalls, kebab shops, fried fish vendors, and sweet shops staying open late into the night, attracting young artists and media workers. This tradition has largely faded, representing another layer of the neighborhood's evolving identity.

Preservation Efforts and Emotional Connections

Local residents are now urging the archaeology department to restore Gawalmandi's heritage structures and designate the old area as a preserved historical site. Imran Asghar, a longtime resident, emphasizes that Gawalmandi symbolizes interfaith harmony among Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs, Parsis, and Christians.

Asghar advocates for repairing the area's hanging electric wires and renovating ancient buildings to attract Sikh pilgrims visiting Panja Sahib, which could also generate foreign exchange. The emotional connection to Gawalmandi extends beyond current residents, as Muhammad Shahbaz, another old resident, notes that Hindu and Sikh families still occasionally visit their ancestral homes, often becoming emotional and taking soil from their former houses as mementoes.

The 150-year-old Gawalmandi Bridge over Nullah Leh, rebuilt three times after flood destruction, has witnessed visits from numerous national leaders including Ayub Khan, Yahya Khan, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, Benazir Bhutto, Nawaz Sharif, Shahbaz Sharif, Ziaul Haq, Mohammad Khan Junejo, and Shaukat Aziz during flood inspections.

As trees now grow through the walls of old houses and heritage continues to decay, the call grows louder to preserve this unique neighborhood that represents a microcosm of Pakistan's diverse history and the potential for interfaith coexistence.