The intricate tapestry of Pakistan's present is woven with threads from its complex past. Understanding the nation's current trajectory requires a deliberate look backward, examining the historical forces, decisions, and events that have collectively shaped its institutions, identity, and challenges. This historical perspective is not merely an academic exercise but a crucial lens for interpreting contemporary realities, from governance and foreign policy to social cohesion and economic development.

The Colonial Inheritance and the Birth of a Nation

The partition of British India in 1947 remains the foundational event that defines Pakistan's geopolitical and demographic contours. The trauma of mass migration, the violence that accompanied birth, and the unresolved dispute over Kashmir were not just initial crises but established enduring patterns. The administrative and bureaucratic structures inherited from the colonial era, often designed for control rather than empowerment, continued to influence statecraft. Furthermore, the ideological underpinning of the nation—the Two-Nation Theory—set a precedent for defining national identity in primarily religious terms, a theme that has echoed through subsequent constitutional and political debates.

Early nation-building efforts were immediately tested by the need to integrate diverse regions and populations into a cohesive whole. The language movement in East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) highlighted the tensions between centralizing forces and regional identities. The eventual secession of Bangladesh in 1971 was a pivotal moment that forced a profound national introspection about federalism, representation, and the very definition of Pakistani nationhood. This loss permanently altered the country's geography and self-perception, leaving a legacy that informs center-province relations to this day, particularly concerning Balochistan and Sindh.

Political and Military Legacies: A Recurring Pattern

Pakistan's political history has been marked by a cyclical interplay between democratic experiments and prolonged periods of military rule. Each martial law regime, from Ayub Khan to Pervez Musharraf, left an indelible mark on the state's structure. These periods often centralized power, altered constitutions (most notably the 1973 Constitution under Zulfikar Ali Bhutto and its subsequent amendments), and prioritized strategic state security over democratic consolidation. The legacy of the Afghan jihad era of the 1980s, supported internationally but with profound domestic consequences, reshaped society, influenced religious discourse, and left a complex security dilemma that persists in the form of militancy and extremism.

The democratic transitions, while celebrated, have often been fragile, grappling with the institutional imbalances created during authoritarian interludes. The repeated dismissal of elected governments, a practice rooted in early constitutional history, has undermined political stability and continuity. This historical pattern of interrupted democracy has fostered a culture of political short-termism and weakened the development of strong, accountable civilian institutions, a challenge that continues to confront the political system.

Socio-Economic and Cultural Echoes of History

Economically, policy choices from past decades continue to resonate. The nationalization of industries in the 1970s altered the landscape of private enterprise and investment for generations. Later, the economic liberalization of the 1990s and early 2000s, while integrating Pakistan into the global economy, also exacerbated inequalities. The historical neglect of consistent investment in education and human development, compared to other national priorities, is a key factor behind contemporary challenges in workforce skills, innovation, and social mobility.

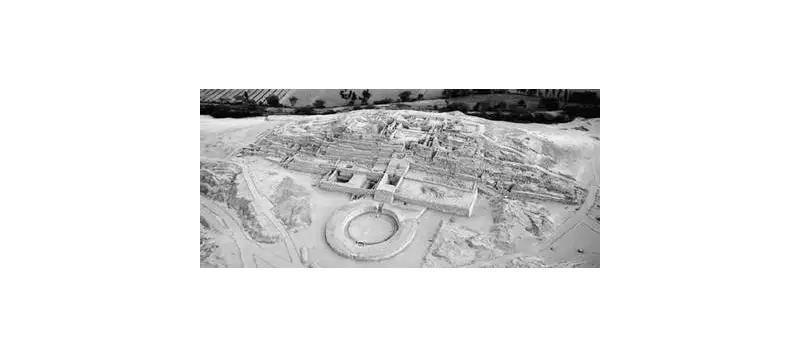

Culturally and socially, Pakistan is a palimpsest where ancient Indus Valley civilizations, Islamic heritage, Sufi traditions, and various regional folkways coexist. This rich, layered history is a source of immense pride and diversity but also of tension when competing visions of national identity clash. The historical evolution of the role of religion in public life, from a unifying principle during independence to a more contested domain of law and policy, remains a central and often divisive theme in national discourse.

In foreign policy, the longstanding relationship with major powers, initially with the US during the Cold War and more recently with China through CPEC, and the enduring rivalry with India, are all deeply historical constructs. These relationships are not based on present-day calculations alone but are burdened by the weight of decades of alliances, conflicts, and mutual suspicions.

Conclusion: The Past as a Guide, Not a Prison

Ultimately, a 'past perspective' on Pakistan reveals that history is not a closed chapter but an active participant in the present. The challenges of institutional reform, economic equity, national cohesion, and democratic resilience cannot be fully addressed without acknowledging their historical roots. However, this perspective also highlights the nation's resilience and capacity for change. Understanding this legacy is the first step toward learning from it—distinguishing between burdensome patterns that must be broken and enduring values that can be built upon. For Pakistan, the past offers critical lessons for navigating an increasingly complex future, emphasizing that while history sets the stage, the script for tomorrow remains to be written by the choices of today.