Pakistan's external account swung into a surplus in November 2025, but the positive headline figure conceals deepening structural economic vulnerabilities. The nation recorded a current account surplus of $100 million, a reversal from a deficit of $291 million in October. However, this modest improvement was not driven by a thriving export sector but almost entirely by the hard-earned money sent home by overseas Pakistani workers.

A Surplus Built on Remittances, Not Exports

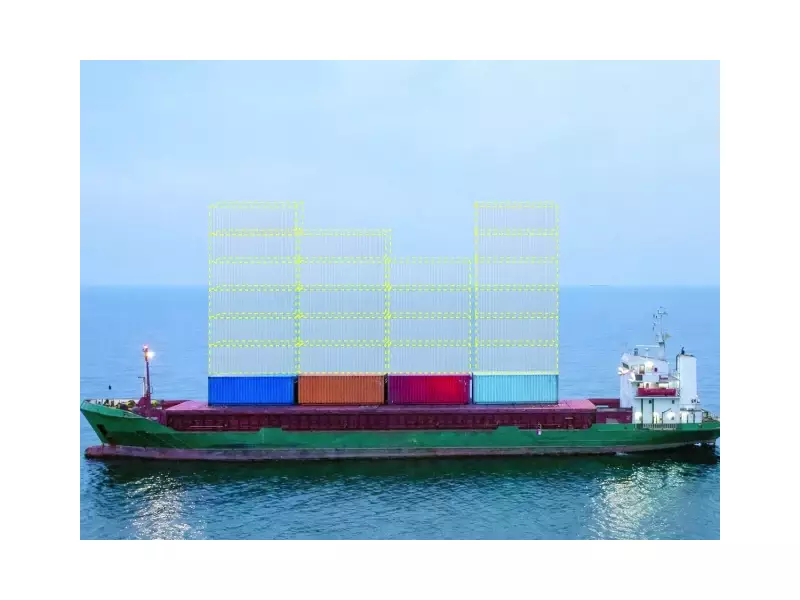

Beneath the surplus lies significant stress on the trade front. Data from the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) reveals a worrying picture: goods exports in November stood at $2.27 billion, while imports ballooned to $4.73 billion. This resulted in a substantial trade deficit of $2.45 billion for the month alone. Exports contracted by 18.5% compared to the previous month, highlighting severe competitiveness challenges, high energy costs, and weak global demand.

The external account remained in the black solely due to robust inflows in the secondary income account, dominated by workers' remittances. Remittances reached $3.19 billion in November, lifting total secondary income to $3.46 billion. This massive inflow was enough to offset the large deficits in goods, services, and primary income. Cumulatively for the July-November period of FY26, the current account showed a surplus of $578 million, a stark improvement from a $1.88 billion deficit in the same period last year, underscoring the decisive role of the diaspora.

The 'Dutch Disease' Trap and Economic Stagnation

Economists like Atif Mian warn that this heavy reliance on remittances, which bring in around $38 billion annually (roughly 10% of GDP), is creating a dangerous economic trap akin to 'Dutch disease.' The large inflows fuel consumption but not productive capacity, leading to an overvalued Pakistani rupee. This overvaluation, in turn, undermines the competitiveness of export sectors like textiles, weakening them further.

The consequence is a vicious cycle: the economy becomes increasingly dependent on continuous remittance flows to support foreign exchange reserves and household spending, while productive investment in manufacturing and exports is discouraged. Mian points to Pakistan's persistently low investment-to-GDP ratio as a direct outcome. The status quo benefits elites in rent-seeking sectors, offering little incentive for the broad-based reforms needed for sustainable growth.

Migrant Labour: The Unsupported Backbone of the Economy

The surplus underscores Pakistan's growing and precarious dependence on its overseas labour force, which receives little to no institutional support from the state. Many migrant workers face systemic hurdles, harassment, and mistreatment from authorities, including the Federal Investigation Agency (FIA). Employed often in tough conditions in the Gulf and other regions, they contend with job insecurity, delayed wages, and limited legal protections.

Analysts note that the surge in remittances may not indicate improved migrant welfare. Instead, it may reflect greater financial strain on overseas workers, who are sending a larger share of their earnings home to support families battling inflation and stagnant incomes in Pakistan. Despite these headwinds, their remittances have become the economy's first line of defence against external shocks, accounting for over 93% of total secondary income inflows in November.

The November surplus provided marginal relief to the country's foreign exchange reserves. SBP's gross reserves increased to $15.86 billion by the end of the month. However, heavy primary income outflows, mainly interest payments on external debt which amounted to $817 million in November, continue to exert pressure and raise concerns about long-term debt sustainability. The path forward requires moving beyond remittance dependence to rebuild a competitive export economy.